Research News

‘Colored microbubbles’ to help doctors see inside our bodies

By CORY NEALON

Published November 8, 2012 This content is archived.

UB researchers, working in collaboration with University Health Network in Toronto, have developed a novel contrast agent that could redefine what’s possible in the evolving field of medical imaging.

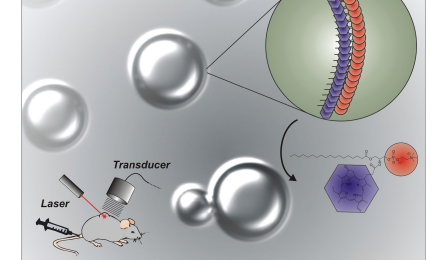

The contrast agent, called “porshe microbubbles,” breaks ground because it can be used jointly to create ultrasound images such as a sonogram, and images from an emerging technology called photoacoustic tomography (PAT). The result—a more detailed, nuanced picture of what’s happening inside the body—could help doctors treat everything from hypoxia to cancer.

“We’re only scratching the surface of what is possible,” says Jonathan Lovell, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at UB and co-author of “Porphyrin Shell Microbubbles with Intrinsic Ultrasound and Photoacoustic Properties,” which appears on the Oct. 10 cover of the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Co-authors include Chulhong Kim, assistant professor of biomedical engineering, and Mansik Jeon, postdoctoral associate in biomedical engineering, both at UB, and four collaborators from Toronto.

Doctors use ultrasound—an effective, relatively inexpensive and minimally invasive imaging technique—for a variety of purposes, including monitoring fetus development and blood flow in the heart, liver and kidneys of children and adults. Doctors often employ microbubbles, which are tiny bubbles of fluorinated gas injected into a patient’s bloodstream, to sharpen the grainy black-and-white images produced from ultrasound.

PAT imaging, by contrast, is a much newer technique. Doctors use pulsed laser lights to generate pressure waves that, when measured, provide a more in-depth view of what’s occurring inside the body. For example, while ultrasound can measure blood flowing through an organ, PAT can measure the oxygen levels in the blood.

Because the two techniques are complementary, there is growing interest to combine them, Lovell explains. The most likely way to accomplish that would be to create “colored microbubbles,” a contrast agent that would sharpen ultrasound images and not interfere with PAT imaging, he says.

Lovell, Kim, Jeon and others created such a contrast agent by encapsulating microbubbles in a shell of porphyrin—an organic compound that strongly absorbs light—and phospholipid—a fat similar to vegetable oil. The result is porshe microbubbles.

“The early tests we’ve done look very promising. I think the next step is to figure out how we can take advantage of this, figuring out what the best applications are,” Kim says.

One possibility entails using porshe microbubbles to analyze the effectiveness of chemotherapy. Instead of waiting weeks for the results, doctors could know within days, Lovell says. Another potential use involves monitoring people who suffer from chronic low blood-oxygen levels, or hypoxia.

“We’re really not sure how the technology will be used. We are, however, confident it will be a very useful tool, especially in medical imaging,” Lovell says.